Turning a scourge into an energy resource

Typha is an invasive species that has invaded a large part of the Senegal River delta and is spreading rapidly. By limiting fishing and cultivation areas and threatening local biodiversity, this environmental scourge has not been controlled for three decades and cannot be eradicated. For several years now, GRET and its local partners have been implementing an innovative strategy to transform this scourge into an opportunity by using typha as a fuel. Here is how…

Rapid and uncontrollable progress

The construction of dams in the Senegal River basin, in particular the Diama anti-salt dam built in 1986, has of course brought many benefits, particularly for the irrigation of agricultural land and the supply of drinking water to the population. But it has been accompanied by the spread of a new invasive species: typha, whose scientific name is typha australis. This fast-growing reed, previously prevented by the salinisation of the water, now covers an estimated 100,000 hectares of the entire basin. And when it is uprooted, this plant is capable of growing back in eight to ten months!

A serious threat to biodiversity, due to the eutrophication of the environment and the degradation of water quality, typha is also increasingly a major constraint for socio-economic activities along the river and a health risk:

- Decrease of agricultural surfaces and obstruction of irrigation channels

- Reduction of fishing areas

- More difficult access to water for livestock

- Increased risk of flooding, due to water stagnation caused by the proliferation of the plant

- Development of certain diseases, transmitted by mosquitoes such as malaria or parasites, such as bilharzia, in water that is more stagnant.

This wild plant cannot be eradicated. Other plant or animal species could a priori counteract its expansion, but more research is needed to assess their full impact on the ecosystem. Others are too costly or harmful, such as chemical solutions that would only aggravate the problem.

Valuing typha and making it an ally

People are already using typha in an artisanal way to create mats, fences or false ceilings. But the solution will only be sustainable and effective if it is based on a large-scale exploitation strategy and leads to an industrial activity.

Two ways of transforming typha into raw material are being tested:

- As fuel for domestic cooking and industrial uses,

- As a building material with insulating properties.

The use of typha in the form of biofuel has many advantages:

- Developing a new energy resource in this region of Senegal and Mauritania where half of the households use wood or charcoal for cooking. The exploitation of typha shows an interesting yield: 1 hectare can produce about 3 tons of artisanal fuel, and 10 tons of industrial fuel, which is based on a mixture of typha and rice husk;

- Substitute for charcoal: the use of firewood and charcoal for cooking is still widespread in these countries. Its consequences are dramatic on the health of the populations, with domestic air pollution and on the forest resources ; The combustion of typha is less toxic in terms of particles and carbon monoxide. And, in terms of environmental impact, for each ton of typha biofuel produced, 7 tons of wood are saved!

Menace sérieuse pour la biodiversité, par l’eutrophisation des milieux et la dégradation de la qualité de l’eau, le typha constitue aussi de plus en plus une contrainte majeure pour les activités socioéconomiques le long du fleuve et un risque sanitaire :

- Diminution des surfaces agricoles et obstruction des canaux d’irrigation

- Recul des zones de pêche

- Accès à l’eau plus difficile pour abreuver le bétail

- Augmentation des risques d’inondation, en raison des stagnations d’eau causées par la prolifération de la plante

- Développement de certaines maladies, transmises par les moustiques comme le paludisme ou des parasites, comme la bilharziose, dans des eaux qui stagnent davantage.

GRET, an international solidarity organisation serving the most vulnerable, has been working for many years in sub-Saharan Africa. Since 2011, it has been working with two partners, the Institut Supérieur d’Enseignement Technologique de Rosso (ISET) and the Diawling National Park (PND), to develop typha-based fuel production chains, from the study of the production process (from cutting the plant to compressing it into biofuel briquettes) to the establishment of a local production chain and its marketing.

The first stage consisted of setting up several artisanal units in Mauritania from 2011 to 2016 and then in Senegal between 2016 and 2018 thanks to a transfer of skills. The units that continue to operate in Senegal are often run by women’s cooperatives in villages near water points invaded by typha. Typha fuel is only marketed on a small scale, mainly for heating tea, as people are still reluctant to change their habits.

Moving to the industrial stage

The entrepreneurial turn to boost this market has been taken since 2018, within the framework of the new Typha fuel construction in West Africa (TyCCAO) programme. This project, established over 5 years, with funding of over 3 million euros, is led by ADEME. It aims in particular to gain a better understanding of how the plant functions in order to better manage it and sustain recovery chains, as a fuel and material in the construction industry.

For the energy component, GRET, which is piloting the project, has relied on a local entrepreneur in the Rosso region (Mauritania) to set up an industrial unit, with a target of 1,000 tonnes of typha and rice husk-based biofuel per year.

“Our experience in setting up small-scale and industrial biofuel production chains based on typha has led to innovative, affordable and renewable solutions for cooking energy as a substitute for wood energy.”

Maud Ferrer, head of Biomass-Energy and Waste projects at GRET

Nevertheless, to optimise their impacts, three major challenges remain to be addressed within the framework of this programme:

- The organisation of typha supply: typha cutting is manual and carried out under difficult conditions. Farmers, who can earn additional income by cutting typha, need to be trained to disseminate cutting skills and practices. Research is also needed to mechanise the cutting process and achieve satisfactory volumes of typha for the production plant; the process of drying and transporting the typha to the plant must be improved with the stakeholders to optimise the yields and profitability of activities;

- Searching for the best economic model to deploy sustainable chains: optimising the quantity of typha cut, allowing the actors in the chain to meet their needs and ensure that the end customer receives a product of affordable quality;

- Raising awareness to change culinary practices, which are deeply rooted in the local culture.

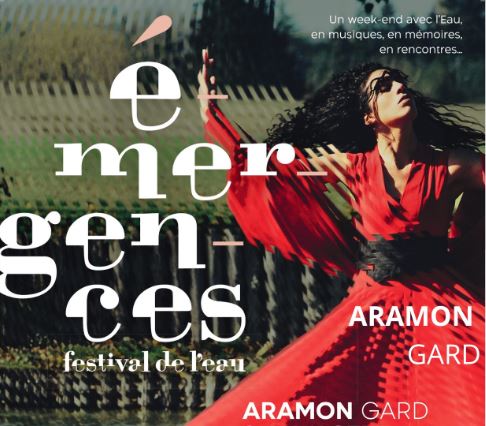

Emergences Festival de l’Eau

Première édition d'un rendez-vous musical et convivial incontournable : le festival Emergences à Aramon, au bord du Rhône près d'Avignon. Au programme du 9 au 11 septembre : concerts gratuits, ballades, conférences... et plus encore !

Agir pour le Vivant, Vienne – 21-23 July

Come and talk about the Rhone and the great rivers in this artistic and friendly festival! Agir pour le Vivant will take place at the Musée Gallo-Romain in Vienne from 21 to 23 July. An opportunity to discover the very first stand dedicated to Living with Rivers, and to protect the rivers together.