Stratégies Saint-Laurent, a network to protect the St. Lawrence River

Stratégies Saint-Laurent is a key player in the governance of the St. Lawrence River. Composed of twelve ZIP Committees (Comités ZIP – Areas of Prime Concern)* in Quebec, it promotes interregional and national cooperation as well as the involvement of local communities along the river to preserve it. An educational component was quickly added to these two main missions, to make all users of the river aware of its strong contribution to the development of Quebec but also of its vulnerability. Jean-Éric Turcotte, Director General of this innovative organization, tells us about the pressures that weigh on the St. Lawrence today and the solutions that are developed to deal with them.

The St. Lawrence is primarily seen as a transportation route, both fluvial and maritime, with its large estuary and gulf. Has the identity of the St. Lawrence primarily been built around navigation?

Not at all! The St. Lawrence is Quebec’s ecumene: 80% of the population lives on its shores or tributaries, so it is above all a living environment. The river also provides food thanks to hunting and fishing, an extremely valuable resource for world exports and for Quebecers. The St. Lawrence is at the core of Quebec’s identity. It is the cradle of historical and cultural sites, but also a source of recreation and entertainment: sea kayaking (Route Bleue), sailing, cruising… The St. Lawrence entertains and inspires. It is also an immense reservoir of biodiversity, one of the richest environments in North America, but in a vulnerable situation. Finally, the St. Lawrence is a source of drinking water for more than 50% of the population of Quebec, in the freshwater section, of course.

Key facts about the St. Lawrence

- Source : Lake Ontario.

- Mouth : Gulf of St. Lawrence, Atlantic Ocean.

- Average flow : 7,543 m3/s (Cornwall); 12,309 m3/s (Quebec)

- Length : 1,197 km.

- Catchment area : 1,600,000 km².

- Crossed states : United States, Canada.

- Tributaries : 244. The main ones are Saguenay, Manicouagan, Saint-Maurice, and Rivière aux Outardes.

You talk about vulnerability. What is the state of St. Lawrence biodiversity? What are the new threats to its ecosystem?

Thanks to the work carried out under the St. Lawrence Plan, we have monitored environmental indicators and we can say that the state of health of the St. Lawrence has improved overall since 1988. This improvement is tangible, with the successful reintroduction of the striped bass, a species that had disappeared from the waters of the St. Lawrence since the 1960s. Another example is the rehabilitation of swimming areas to even higher standards than before, which allows people to return to activities that bring them into contact with the river.

But the river remains vulnerable. In the deep waters of the gulf, there is a problem of hypoxia, i.e. a significant loss of oxygen, which causes certain species to suffer. There is also the development of invasive alien species : Asian carps, Japanese knotweeds, round gobies, etc.

The St. Lawrence is also becoming increasingly artificial especially in the river part, with urban areas, ports, highways, etc. This trend is causing losses, especially in wetlands, which will jeopardise this ecosystem for many years to come. Even today, the law for the protection of wetlands is not completely effective. And this has a direct impact on certain species. The loss of habitat has a direct impact on vulnerable species. Some of them have nowadays a endangered species status, such as the copper redhorse and beluga whales, which have been officially endangered since 2016.

There are also new anthropogenic pressures linked to the emergence of pollutants. The interest in plastic pollution in the St. Lawrence is very recent, even if it is one of the rivers most affected by plastic on a global scale. Other pollutants are also discharged: oestrogens, antibiotics, pesticides, chemical products, etc. Some products are banned, but the persistence of certain substances suggests long-term effects. This is the case for flame retardants which are used in household products and that you can still find in its ecosystem.

There are also problems of overfishing, even if management has improved considerably over the last thirty or forty years. Cods and other species such as yellow perch, particularly in Lake Saint-Pierre, have experienced worrying declines. These declines are attributable to poor management of agriculture in flood-prone areas.

But the solutions are there: better planning of river management is needed, so that it is integrated and considers the cumulative effects of projects as well as climate change. We must continue to develop protected areas and change the behaviour of both decision-makers and users, to make the St. Lawrence an exceptional heritage that must be protected.

“The important thing to protect the river is to have a range of tools and stakeholders.”

Jean-Eric Turcotte

You mention significant pressures on the river’s wetlands, which could benefit from protected areas statuses. How far have you got in the basin?

There are many initiatives to protect wetlands and they would benefit from being reinforced by legislation and investment. On a global scale, Canada is not at the top of the class in establishing marine protected areas! However, there has been an improvement recently. But it still needs sufficient funding and coherent networks to be effective. As a representative of the St. Lawrence Action Fund (SLF), an organisation that aims to finance conservation projects, I can see that government efforts are beginning to emerge but are still far from sufficient. Only 1% of GDP is dedicated to environmental protection.

How can we explain the hypoxia phenomenon in the St. Lawrence waters? Is it due to agricultural discharges, pollution from shipping?

There are specific causes. It is true that agricultural water enriches and deteriorates the St. Lawrence. But in a more systemic perspective, the mixing of waters in the St. Lawrence has evolved. In the past, the Gulf was largely made up of cold, highly oxygenated water from the great cold currents that flow down from the Labrador Strait – almost from the Arctic. For several years now, there has been more water coming from the Gulf Stream, which is less well oxygenated. This global change in the major currents is due to climate change, among other things. In fact, we have few means of intervening in such global events. We must therefore continue to work on what we can control, such as water over-enrichment.

How are coastal communities adapting to the effects of climate change, in particular the reduction in fish stocks and rising sea levels?

As the St. Lawrence plain is populated by large cities such as Montreal, it affects a large part of the population. Riverside residents have observed that the overall water regime of the St. Lawrence has changed. This is also the case for its tributaries, such as the Ottawa River and the Great Lakes where we alternate between periods of unprecedented flooding and drought. This has a cost for populations that have historically settled in flood-prone areas, at a time when there was little knowledge and awareness of these issues. It also creates conflicts over the use of the water of the St. Lawrence. There is a system of locks and means of controlling water levels between the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence, to allow navigation between these two ecosystems which are not at the same level. Managed by international agreements between the United States, Canada and Quebec, this system is important for maintaining adequate water levels – during low water periods, the first conflicts emerge.

And in the marine environment, it is the opposite: when you don’t have enough freshwater, you have too much saltwater! In several communities in the estuary and gulf, there are periods of flooding and erosion, accentuated by global warming. These changes in the regime have, for example, had a very real impact on shoreline ice (ice floes) on the St. Lawrence. During major autumn storms, this ice used to act as a natural shield against storms. Now, as the ice forms later, shorelines suffer significant damage, including in densely populated areas.

What role can citizens play in responding to these changes?

The first role of citizens is to ask the right questions. How are the riverbanks being developed, with what vegetation? How do we treat wastewater, especially brown water? Stratégies Saint-Laurent and ZIP committees play a role in raising awareness of these issues, but also in reclaiming the river: a known river is a river that can be protected.

The second means available to citizens is the vote: the democratic voice makes it possible to mobilize local, provincial and federal governments that are aware of and responsible for climate issues. Governments that are prepared to take consistent action, to invest in the environment and to manage the land better.

Finally, citizens can also take action directly: for example, recently, the LNG Quebec project, intended for natural gas exports, was abandoned thanks to the mobilisation of citizens and First Nations representatives.

One of the missions of Stratégies Saint-Laurent is to reappropriate the river. Has this link with populations weakened over time?

The slogan of Stratégies Saint-Laurent is “Giving the St. Lawrence back to his people”. We want to provide means of restoration and conservation to bring the St. Lawrence back to a sustainable state. But it is also about putting the river back in the hands of the people, so that they reconsider it as something essential. There was a gap between the 1950s and the 1990s, when the well-being of the river was not at the centre of discussions: today we are paying the price. In recent years, thanks in particular to the hard work of groups like Stratégies Saint-Laurent and the twelve ZIP committees, this reappropriation has taken place. I can see it thanks to the popularity of a network like ours. Citizens are acting: they march for the St. Lawrence, the vote differently, and they participate in local projects, such as Operation St. Lawrence, highly successful shoreline cleanups with partners such as Mission 1000 Tons.

OPERATION ST. LAWRENCE, AN INTEGRATED INITIATIVE

Operation St. Lawrence is a major cleanup campaign to remove waste, especially plastic, from the riverbanks, in cooperation with other actors such as Mission 1000 Tons, WWF and the ZIP Committees.

- Cleaning up the riverbanks

- Raising awareness among schools and parents

- Creation of passports of commitment for citizens and encouragement to reduce single-use plastic

- Certification system for 70 member companies

But as far as the authorities are concerned, although there has indeed been a change in discourse, we are still waiting for action and, above all, for substantial budgets. Positive signals are being sent out via the support of Avantage Saint-Laurent (provincial) or the Coastal Restoration Fund of the Oceans Protection Plan (federal). These initiatives must be improved if we do not want to quickly find ourselves with our backs against the wall!

“For the St. Lawrence, the sense of urgency must increase”

You work to restore the ecosystems of the St. Lawrence, develop protected areas and protect wetlands, with shoreline residents, local communities, government levels… And what about the economic players?

We also work with them! For example, we are contributing to the development of the Alliance Verte, a certification for maritime transporters that has been a real flagship in Quebec. This non-profit organisation (NPO) was mandated by a portion of the maritime industry and the St. Lawrence Economic Development Corporation (SODES). It proposes some fifteen indicators that evolve and allow for the gradual improvement of maritime industry practices. The certification was so well received that it was extended to the whole of Quebec, and then to the United States, South America and Europe under the name Green Marine. It is an initiative that could also be inspiring for other economic sectors.

All over the world, the recognition of rights to nature is advancing. A first initiative in this direction was carried out in Quebec in February 2021 for the Magpie River. A bill was also recently tabled to give rights to the St. Lawrence. In your opinion, what is the point of using legal leverage to protect the river?

It is an absolutely necessary means, but also an acknowledgement of failure: to put a status on a territory is to underline that one is not responsible enough to use its resources in a sustainable way. Nevertheless, I believe in these projects, and Stratégies Saint-Laurent has contributed to this initiative of the International Observatory for the Rights of Nature (IOLN), notably by contributing to the reference work: A Legal Personality for the St. Lawrence River and the Rivers of the World.

Other long-standing initiatives are also an important legal force. Although Canada is not ahead of the curve, marine protected areas are interesting developing tools. The Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park, for example, is a Canadian jewel, born from the collaboration of two levels of government, the SÉPAQ, a Quebecker state corporation, and Parks Canada, a federal government agency. We hope to see more initiatives like this one.

There are about twenty different statutes to protect natural areas: Canada has no shortage of tools. But many sensitive areas are not yet protected. There are other interesting political initiatives: in March 2010, Parti Québécois MP Scott McKay tabled a motion in the National Assembly to have the St. Lawrence recognised as Quebec’s national heritage. The motion was unanimously adopted, which is unusual and shows the interest and awareness of Quebec’s elected officials. But this status did not lead to any really concrete results… This did not prevent decisions from continuing to be taken in silos.

“I hope that the political will will be there. […] I look forward to seeing the concrete results of this initiative of the International Observatory for the Rights of Nature for the St. Lawrence.

It is also important to consider the involvement of the First Nations, who play a crucial role and who must be involved in the definition of the initiative and its implementation.

And you, Jean-Eric Turcotte, what is your relationship with the St. Lawrence river?

I have both an emotional and professional connection to the river. I’ve been working around the river for 25 years, at the head of Stratégies Saint-Laurent and as director of the Foundation dedicated to the St. Lawrence. But I am above all a child of the river: my family comes from the Lower St. Lawrence, in the riding of La Mitis in Sainte-Flavie. I spent my entire childhood gathering shellfish, going fishing and swimming in the cold water. Before embarking on a career, I studied the river, and more precisely coastal and marine geomorphology at Laval University! And I also practice activities on the river: sea kayaking, photography, birdwatching… The river is part of my daily life. And it’s a bond that I’ve also passed on to my children: one of my sons now works for the Société des Traversiers du Québec.

And if the St. Lawrence were a character, how would you describe it?

I see it as a vulnerable giant: “a river of great waters”, to paraphrase Jean-Frédéric Bach, but a giant that is under quite a bit of pressure and is showing signs of fatigue.

*The ZIP committees are regional consultation and action organizations whose mandate is to bring together the main users of the St. Lawrence in their territory and to encourage them to work together to solve local and regional problems affecting river ecosystems and their uses.

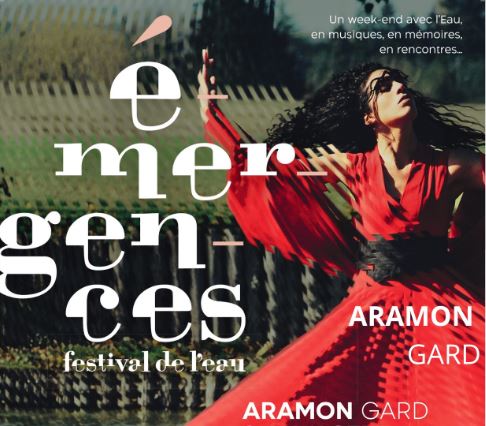

Emergences Festival de l’Eau

Première édition d'un rendez-vous musical et convivial incontournable : le festival Emergences à Aramon, au bord du Rhône près d'Avignon. Au programme du 9 au 11 septembre : concerts gratuits, ballades, conférences... et plus encore !

Agir pour le Vivant, Vienne – 21-23 July

Come and talk about the Rhone and the great rivers in this artistic and friendly festival! Agir pour le Vivant will take place at the Musée Gallo-Romain in Vienne from 21 to 23 July. An opportunity to discover the very first stand dedicated to Living with Rivers, and to protect the rivers together.