A meeting with Mamoudou Kane, photographer and journalist.

The geographical border between Mauritania and Senegal, the river nonetheless remains an element of the identity of the communities that people its banks, whatever their nationality. Mamoudou Lamine Kane, a photographer, poet and journalist, likes to speak of his country, Mauritania, by following this path of water, meeting the communities who live from farming, livestock breeding and fishing. For Living with Rivers, he accepted to tell us of these meetings and thus offer a narrative on his country.

You were brought up on the peninsular of Tékane, in Mauritania, on the banks of the River Senegal. Is that where your love of the river springs?

Yes, I come from this village located between the branch of the river connected with Mauritania, the Njawaan, and the River Senegal itself, three kilometres away. Before the bridge was built twelve years ago, it was a peninsular cut off by the water that had to be crossed by canoe. During the rainy season, we calculated all our journeys in terms of about ten days, depending on the rain. As a child, I stayed for two or three months of the summer holidays. There were no roads, no mobile phones: we were cut off from our parents all that time. It was like being in another dimension, where I developed my imagination and a very special relationship with water.

How is your work as a photographer linked to the river?

I tend to think of that the River Senegal speaks of itself, when one sees the life on its banks, the Peuls, Soninkes and Wolofs. Their agriculture, intimate moments, the people that stroll around … I’m aware that throughout the river valley, behaviours have been dictated naturally by sedentarism around the water. That’s what I try to capture in my photographs. What interests me most in my travels is to let the people I meet express themselves. I’m a fan of the Humans project in New York, where the contributors take second place to the stories told.

I also have the impression that the spirit of the people along the river banks is a very different from that of people living inland. I studied in France, and I always found that the Bretons were very different from the other French people. By studying the history of Victor Hugo and his link with Brittany, I understood that there were geographical reasons for this literature, this lifestyle. I have this feeling next to the river Senegal. There is an openness of spirit by the river: everyone speaks at least three languages, and it’s quite usual to speak five or six languages.

And you, what languages do you speak?

I speak Peul, Wolof, French, English and Hassanya, an Arabic local dialect. Between Rosso and Kaédi, the people speak Wolof, Peul, Soninke, Hassaniya, French and English. The capital of Trarza, Rosso, is the melting pot of Mauritania: There are Wolofs, Moors, Haratines, Peuls, Soninkes, etc. They are very mixed communities, where tolerance is essential. You find the same thing in the region of Gorgol, and its capital, Kaédi. The relationship with the river means that the communities have to interact for trading and cultural reasons, but also for survival.

Because the history of the River Senegal is also one of tragic events.

Indeed. Close to the river, if all the large Mauritanian villages look onto Senegal on the other side of the river, it’s because they were Mauritanian enclaves that were created at the time of the Berber raids. Families left the villages on the Mauritanian side to find refuge on the opposite bank. The river protected them from the kidnapping of their children by the Berbers who saw the river as a nursery for slavery.

My village, which was an enclave between two rivers, was doubly protected. Despite what happened, we were totally free. It wasn’t rare, when I was seven or eight, to wander for kilometres, chasing birds, picking cherry tomatoes. We were lucky to have this feeling of safety.

But the raids continued until the 1980s. I know people of my entourage who were kidnapped, children, after having wanted to cross the river. They were found years afterwards as slaves abroad.

The River Senegal is also a geographical border between Senegal and Mauritania.

The border between Senegal and Mauritania was drawn on the occasion of decolonisation, at the Congress of Aleg in 1958. Initially, the border should have been at Aleg, fifty kilometres north of the river on the Mauritanian side. But due to disputes, the river Senegal became the natural border. Everyone was already aware that it was ridiculous! The River Senegal was the living space of the same families on both sides of the river. In the space of a day, thousands of families found themselves with different nationalities.

This separation by the river is recent. The people who’ve lived through it are still alive. Not enough time has passed for the river to have become a genuine dividing line in terms of national and cultural identity.

Hasn’t the river been the theatre of other conflicts, later in the 1990s?

The “incidents” of 1989 effectively took place around the River Senegal. Using the conflicts between the herdsmen and the farmers of both countries as a pretext, the Mauritanian government deported 60,000 Peuls to Senegal. With a wave of a hand, it was decided that they were no longer Mauritanians. It was an excuse to take control over the arable land that bordered the river.

During this dark period, from 1987 to 1991, the Mauritanian government led by Colonel Maaouya Ould Sid’Ahmed Taya practiced a policy of ethnic cleansing in the army, the police and the gendarmerie. Great Peul writers were killed during this period. All the Peul officers were massacred. The few who escaped fled to France and Sweden. Following this attempt at ethnic cleansing, most of those who fled waited until 2008 to return at the instigation of the first democratically elected President of Mauritania, Sidi Mohamed Cheikh Ould Abdallah.

In our village, we were spared for the most part, since the generation of our parents had foreseen what was to happen. We were nearly the only village to have had identity papers issued in anticipation of the expropriation of our lands. My childhood, despite the events of 1989, was quite calm. But my generation is very aware of the stakes represented by this land and the relationship with the Mauritanian authorities. I think that it’s from there that my interest in the life of the peoples who live around the River Senegal comes.

Claims have now been made before the national courts by the widows and child beneficiaries – because it was above all the men who were massacred. But they don’t get very far, and the subject is an element of social unrest.

Nonetheless, a dialogue has been established, partly promoted by international funding organisations like the French Development Agency (AFD) and the World Bank. The most striking example is the development project at Ferallah, in the region of Brakna in the southwest. The World Bank wanted to finance irrigation works on the land that had been taken from the village and given to the Moors during this period. The beneficiaries, who had returned from deportation, took their case to Washington and the project was blocked. We’re speaking of tens of millions of euros on which the Mauritanian government counted greatly. These issues concerning land are now being settled amicably.

What do the peoples who live by the river live on today?

Most of them live from market gardening crops, especially since the great droughts of 1973. These crops are highly dependent on seasonal rains, and thus climate change. Either there isn’t enough water or there’s too much. That’s why the AFD is working a lot on agricultural redevelopments to level the land and allow the storage of water, or on the contrary allow it to flow past and avoid the destruction of the crops.

During the rainy season and the hunger gap*, the men of these communities go to the regional capitals to continue working and send food rations or money to their families who have stayed at home. Whole villages are peopled only by women for four or five months of the year, as I explained in my article, “Villages without men: between food crisis and social mimetics”.

During the rainy season, the lack of infrastructures means that these villages are completely cut off from the world. Even the humanitarian NGOs which carry out activities in these areas prepare in advance: instead of distributing food rations every month, they distribute four or five months in one go before the rains block access to the villages. These enclaved areas are very common in the Gorgol and Guidhimakha regions.

The men who leave in the exodus to the towns often return for the inter-season periods, when the rains have passed and the earth is ready to be sown with corn and wheat. Last year, there was no water: the market garden harvests were disastrous, leading to one of the worst hunger gaps. This year, we’re afraid of having too much water, with abnormal torrential rains in the regions of Gorgol and Guidimakha. It would be a disaster for the market gardening cooperatives.

In contrast, the rain is a reason to rejoice for the herdsmen of the Hodhs regions, Moor regions bordering Mali in the central eastern part of the country. They are also welcome for rice-growing, especially in the regions of Brakna and Trarza in which 90% of Mauritania’s rice production is concentrated.

What do you think are the solutions for stemming this seasonal exodus?

New infrastructures are needed. In Gouraye, the Mauritanian town facing Bakel in the region of Guidhimakha, the expatriated populations have contributed to the financial resources necessary to build greenhouses. This lasting and sustainable infrastructural solution would also increase productivity and protect against the effects of too much light and heat. In May, the temperature reached peaks of 50°C, which destroys market garden crops. But the crops under greenhouses were spared for the most part.

Indeed, solutions must be mixed and combine water sources and greenhouses, as well as technical training and institutional innovations to help reduce the impact of climate change and water shortages.

Major efforts have been made to support farmers and livestock breeders in the north of Senegal to facilitate entrepreneurship. But on the Mauritanian side, it’s more complicated with tensions between the different communities.

During your reporting travels, you also went to N’Diago, a few kilometres from Saint Louis. How is life organised there?

The lifestyle of these people who live on peninsulas between the Atlantic Ocean and the River Senegal is very particular. Geographically, it’s complicated: the islands close to N’Diago are Senegalese while those close to Saint Louis are Mauritian. These communities practice both market gardening and fishing. The triptych between fishing in the ocean, growing crops and livestock breeding is very specific to this region of the estuary between the river and the Atlantic.

For me, this region is the most beautiful and the richest of the river. By looking down from a drone high above, one can clearly see two strips of land, like lines drawn with chalk: the sand of the beach facing the ocean, in sharp contrast with the red clayey river. This boundary also marks two different worlds, two different modes of exploitation, life at sea and life on the river.

Don’t people fish in the river?

The fish fished in the River Senegal is exclusively used for smoking. In Wolof it’s called “gueddj”. The fish is smoked and dried in the sun. It’s then used to give a distinctive taste to rice and fish.

What relationship do the other regions of Mauritania have with water?

Life is very different in the desert areas, where the water sources are wells and drinking troughs for cattle. Likewise for the areas exclusively along the Atlantic coast, in the north between Nouâdhibou and Nouakchott, and for the populations who live around the many ponds of Mauritania.

In the desert, the women dig to find water sources. Sometimes, the quest is fruitless for several weeks. Sometimes, they come across a pocket of water that will serve as a reserve for the village for several months. It’s the dance following this discovery that I was able to photograph and film. This sincere joy where water is a question of survival for those not lucky enough to have a river flowing next to them. In urban areas, where water is obtained from a tap, where one can shover several times a day during heatwaves, we forget the extent to which water is precious.

It will be with great pleasure in the weeks to come that we will receive the reports Mamoudou has produced between Rosso in Mauritania, and Kayes in Mali.

- A report at Nouakchott on the work of the neuro-paediatrician Hala Mohamed Moussa.

- A report for the AFD on the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on the Mauritanian economy and the implementation of assistance measures.

- A collection of poetry, Je suis légion, published by Acoria:

* Hunger gap: in staple crop farming, the period of shortage before the first harvests of the year, when the reserves of the previous year run out).

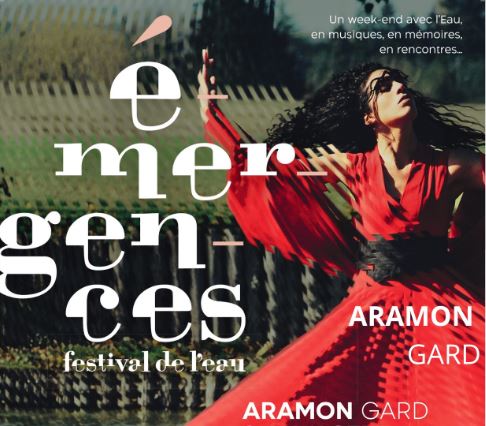

Emergences Festival de l’Eau

Première édition d'un rendez-vous musical et convivial incontournable : le festival Emergences à Aramon, au bord du Rhône près d'Avignon. Au programme du 9 au 11 septembre : concerts gratuits, ballades, conférences... et plus encore !

Agir pour le Vivant, Vienne – 21-23 July

Come and talk about the Rhone and the great rivers in this artistic and friendly festival! Agir pour le Vivant will take place at the Musée Gallo-Romain in Vienne from 21 to 23 July. An opportunity to discover the very first stand dedicated to Living with Rivers, and to protect the rivers together.