Hamed Diane Semega: “We need to put the river’s resources at the service of regional development”

On the occasion of the 9th World Water Forum hosted by Senegal last March, the Organisation for the Development of the Senegal River (OMVS) was awarded the Hassan II Great World Water Prize. This distinction is a recognition of the spirit of the OMVS, which for 50 years has been working to make the river a source of integration and cooperation between the countries it crosses. This unique model, now faced with the new challenges of climate change and demographic pressure. It could serve as an example for other river basins in the world, according to Hamed Diane Semega, High Commissioner of OMVS and member of IFGR, whom we met on the occasion of this major meeting of the world water community.

What does the Hassan II Grand Prize for Water mean to you?

It is a great honour to receive this distinction, which I consider to be the “Nobel Prize of water”. The OMVS deserves it because since its creation in 1972, it has positioned itself as a factor of stability, development and peace building between the four countries that share the river. Above all, it is a model that works, allowing rational and optimal use of water resources in a region with an arid climate and a river with irregular flows.

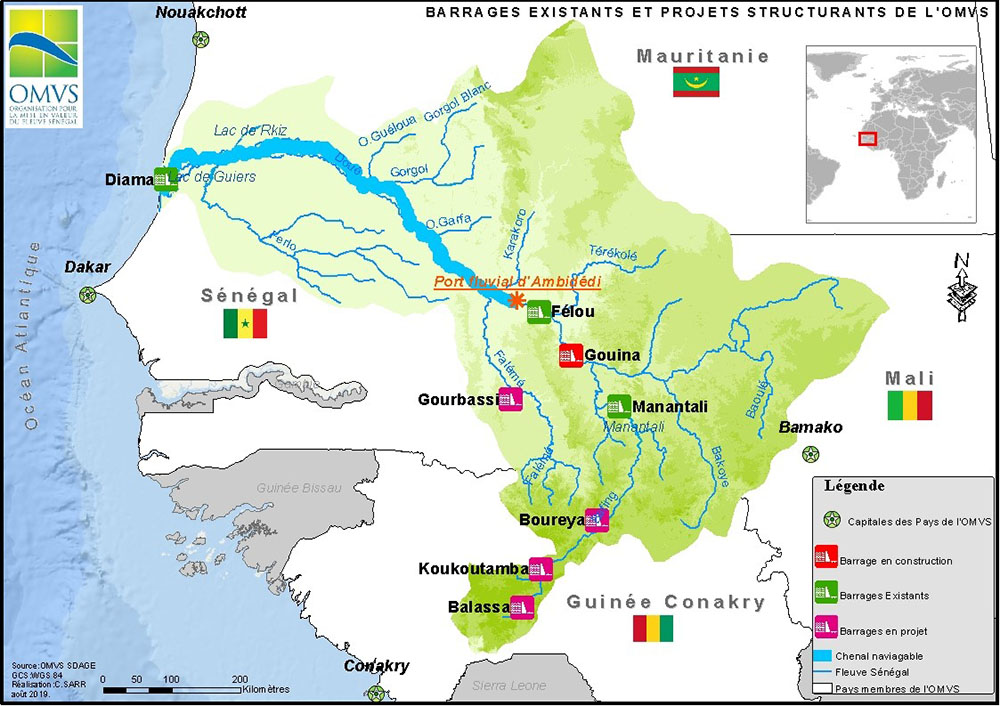

For example, more than 200,000 hectares have been developed for irrigated agriculture, of which 135,000 hectares are currently being exploited. With the hydroelectric schemes, the installed capacity is 400 Megawatts (MW), including 200 MW from Manantali, 60 MW from Félou in Mali and 140 MW from Gouina. These dams and the associated electricity network have made it possible to cover 40 to 50% of Mali’s electricity needs, 20 to 30% of Mauritania’s and 10 to 12% of Senegal’s electricity needs. In 14 years, one billion dollars per year that would have been spent on thermal electricity production has been saved by the member countries!

This prize is also a way for the OMVS to involve the populations more in the preservation of water resources and to make it a political issue, i.e. one that is shared by all.

Everyone speaks of water as a source of life, an element of prime strategic importance, but for all that it is not treated as a central environmental issue, whether from the standpoint of infrastructures or that of management upstream of conflicts.

The essential issue of water is not an issue to be dealt with only by experts, it’s an issue that involves everyone.

What should be done so that water becomes a major political concern and not just confined to experts speaking to each other? In my opinion, every citizen in the world should become aware and change their behaviour to this resource. In Africa, where many areas suffer from water shortages, we don’t feel that this issue is taken into account with the gravity it deserves. Everyone should feel responsible.

Do you believe that water and rivers in particular are still ignored?

Yes, the cause of rivers is struggling to be heard. I would like to pay tribute to all the work done by IFGR, the advocate of rivers, the advocate of the voiceless, to make them better known and recognised.

Because water will be increasingly at the centre of strategic challenges and risks and is likely to give rise to major conflicts. The Fouta-Djalon massif in Guinea is an obvious example. It’s at the heart of the problem of water source availability for the whole of West Africa. The source of the Senegal River lies there, as are the sources of ten other rivers. It continues to become more fragile due to climatic events and human activities. Despite the efforts made through the integrated water resources management programme (PGIRE), the restoration of the vegetation cover of the Fouta Djallon massif remains the main battle to be won. But I don’t have the impression that there is any awareness of the urgent need to stop the damage: the same acts continue to occur at a scale that threatens everyone.This is why we launched, on the occasion of the World Water Forum, a Global Coalition for the Protection of the Fouta Djallon Massif.

How can the OMVS represent a model for river and freshwater resource management?

The OMVS model is unique due to its legal basis which serves to guide all its actions since the creation of the organisation on 11 March 1972. It upholds the river as an international asset.

Furthermore, the structures that have been built along its course belong to the countries indivisibly and severally. For example, a structure built in Mali does not belong to Mali alone: it belongs to Mali, Mauritania, Senegal and Guinea.

The Senegal river belongs to all of us and everything that’s done on the river must be done with the consent of everyone in the OMVS.

This unique model overrides the question of territorial possession. It explains why, 50 years later, the organisation is a source of stability and peace. A lot of people ask how can a cross-border river be managed in a region of the Sahel highly vulnerable to climatic hazards. The availability of water resources is becoming more and more problematic. On the contrary, their utilisation is increasing exponentially at the same time as the demography. The potential for conflict is therefore huge. It’s not a river in a temperate country; it’s neither the Rhone nor the Rhine!

Despite that, there is no conflict linked to using the river’s water resources, quite the contrary. Thanks to the legal basis like the Water Charter-supranational law to which all the uses of the Senegal river’s water are subject – and the permanent dynamics of dialogue, inextricable links have been woven between countries. We share a common destiny.

Is that the explanation of why the history of the OMVS has not been marked by any conflict during its 50 years of existence?

Yes, that’s right. But it must be emphasised that this legal corpus is the manifestation of very strong political determination. Those who replaced the founding fathers of the OMVS could have called this vision of things into question. On the contrary, they consolidated it. We have a heritage that nobody wishes to deteriorate since it is the reason for our strength. Everyone measures the seriousness of an action if it threatens this common heritage.

To go further, I’d say that the OMVS is an act of faith, faith in the future.

For 50 years, this will to cooperate has not been countered by the organisation’s members, despite the vicissitudes of political life.

With the OMVS, we have built the basis of cooperation using a unique legal corpus born from very strong political determination. This model has not only guaranteed the peace of our countries for 50 years, it has also generated wealth.

What direction does the OMVS foresee for the next 50 years? Will the act of faith be renewed?

The Conference of Heads of State held in 2020 at Bamako issued a declaration aimed at consolidating the gains made by the organisation and combating the destruction of ecosystems. Obviously, underlying all that was the idea of ensuring peace through cooperation and still more integration. Over the last fifty years, we have built a family around the Senegal River.

A prospective document is being prepared. The aim is to identify all the sectors in which the OMVS’s action can be used as a lever for integration and speeding up development in the next 235 years.

The structural projects include that of restoring navigation between Saint-Louis and Ambidedi. Where does it stand at the moment?

This project is the missing link in the dynamics of developing the Senegal River basin. We want this space to become a place of economic and human integration that prefigures African integration on a larger scale. The navigation project is the most structural project as it gives real substance to all the other projects that have already emerged (irrigated farming and hydroelectricity). The project is progressing and IFGR is helping us substantially. We are currently waiting for the funding to be finalised, and it’s on the right track.

The first phase of the project will last three years. It entails dredging the river along 905 km, from Saint-Louis to Ambidédi, and building a channel and a river-maritime port at Saint-Louis to transport goods to Mali. On either side of the two banks, in Senegal and Mauritania, in the second phase we want to develop mineral transport. The mines are not viable at present due to the cost of transport. It’s an ambitious project but our political determination matches our ambition. It will be carried out for the well-being of the basin’s populations, and especially historic towns like Podor and Matam, which should recover their economic vitality.

The OMVS is a candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize. Is this candidacy, supported by IFGR, motivated by this founding model?

Like Switzerland, the symbol of hydro-diplomacy on the global level, we want “blue peace” to be the reference. The peace of river basins is the substrate on which more global peace can be built. When sharing water, especially in a situation of scarcity, we develop synergies that lead to finding consensus on other subjects. Rivers must be vectors of peace.

The OMVS has proved the solidity of its model, a generator of peace and wealth. The investments in structures, which require sacrifices, have led to the development of irrigated farming: hundreds of thousands of hectares of farmland have been developed by slowing down the advance of saltwater thanks to the Diama dam, for example. Dams like that of Manantali also provide hydroelectricity that we sell to the electricity companies of the member States. Also, cities like Dakar in Senegal and Nouakchott in Mauritania, depend on the river for their drinking water. The electricity lines that transport the current inland to Mali and to the capitals on the coasts are another good illustration.

Et c’est possible ! Notre modèle a déjà inspiré celui de l’Organisation pour la Mise en Valeur de la Gambie (OMVG), qui est aussi devenue une référence. L’expression de la volonté politique d’assurer la paix aurait pu être un vœu pieu si elle ne s’était pas accompagnée de réalisations concrètes. Ce sont elles qui ont donné corps à cette vision de coopération et de stabilité.

If the OMVS wins the Nobel Peace Prize, what progress will it enable for managing water resources elsewhere in the world?

It would be a wonderful echo for the peace of river basins. It could inspire others to build a similar model: the basins of the Nile, Mekong, and Jordan, for example. Men have built this model, not supermen.

And it’s possible! Our model has already inspired that of the Gambia River Development Organisation (OMVG), which has also become a reference. The expression of the political determination to ensure peace could have been nothing more than a pious wish if it were not accompanied with concrete acts. It is these acts that give substance to this vision of cooperation and stability.

The Nobel Peace Prize will permit shedding light on the fact that, for 50 years, we have cooperated in the harsh environment of the Sahel on an increasingly rare resource without going to war with each other.

A unique organisation for the 2nd most important river in West Africa

The Senegal River is the second most important river in West Africa after the Niger River. Its basin is 1800 km long and covers an area of more than 300,000 km2, ranging from the humid tropical zones in the Guinean part to the dry tropical zones. It crosses diversified biophysical environments from the high basin in the Fouta Djallon mountains (the water tower of West Africa) to the delta, passing through sub-desert zones.

The watershed is home to about 4 million people who derive most of their income from the resources of the environment.

The OMVS was created in 1972 by Mali, Mauritania and Senegal, joined in 2006 by Guinea.

Its missions:

- Reduce the vulnerability of the economies of member states to climatic hazards and external factors

- Preserve the balance of the basin’s ecosystems

- To contribute to the food self-sufficiency of the populations

- Contribute to the economic and social development of member states

- Secure and improve the incomes of these populations.

Emergences Festival de l’Eau

Première édition d'un rendez-vous musical et convivial incontournable : le festival Emergences à Aramon, au bord du Rhône près d'Avignon. Au programme du 9 au 11 septembre : concerts gratuits, ballades, conférences... et plus encore !

Agir pour le Vivant, Vienne – 21-23 July

Come and talk about the Rhone and the great rivers in this artistic and friendly festival! Agir pour le Vivant will take place at the Musée Gallo-Romain in Vienne from 21 to 23 July. An opportunity to discover the very first stand dedicated to Living with Rivers, and to protect the rivers together.